Corey Crawford paid his dues, and now he's getting the respect he deserves

Success hasn’t come easy to Crawford, even if his critics say it has because he plays on a loaded Hawks team. There was a time he wasn’t sure he was going to make it – a time when every mile logged on the bus in the minors seemed to take him further from the NHL.

Corey Crawford paid his dues, and now he's getting the respect he deserves

Corey Crawford paid his dues, and now he's getting the respect he deservesAt some point, this season or next,

Dustin Tokarski is going to skate out and take his spot in the crease for his 256th game in hockey’s minor leagues. When it happens, there’s a good chance

Corey Crawford won’t notice. Why would he? The guy is a big shot now, with two Stanley Cups under his belt and probably more coming. He’s pulling down $6.5 million large, with another $23 million coming over the next four years. He has full control of the net and the unwavering confidence of the franchise that has set the gold standard for all others in the NHL. Why should he care about some journeyman backup making a start in the minors on Tuesday night in Bakersfield or Elmira or playing against something called the Greenville Swamp Rabbits? Here’s why. Because when Tokarski finally plays that game – he was at 249 and the third goalie for the San Diego Gulls in the AHL – Crawford will finally be able to say that somebody in this freakin’ goalie business has played more games in the minors than he has. Of the 86 goalies who had appeared in the NHL this season as of mid-March, not a single one had played as many games in minor pro backwaters as Crawford had. For five years, spanning 255 games, Crawford played in the minors, first in Norfolk, Va., then three years in Rockford, Ill., a place whose claim to fame is Home of the Sock Monkey.

Crawford is a lightweight compared to, say, Johnny Bower, who spent seven seasons in the minors and was rewarded for his efforts by playing for the last-place New York Rangers for a full season. Then he spent four more years in the American and Western Leagues, with a handful of starts in New York, before joining the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1958. According to Bower’s birth certificate, he didn’t find his place permanently in the NHL until two months before turning 34. Crawford was a couple months shy of his 26th birthday before he found a permanent home with the Chicago Blackhawks, despite having the worst birthday possible in hockey – Dec. 31. Nobody with that birthday is supposed to make the NHL in the first place.

But Crawford is accustomed to doing it on his own. He was just 15 when he was forced to leave his home on the south shore of Montreal to play midget hockey two hours away in Gatineau, a move that was necessary because his town of Chateauguay fell into Gatineau’s catchment area. So if a team two hours away from his home wanted him, he had to play there rather than one 20 minutes from his house. The son of a social services worker for the Quebec government and a student services officer at McGill University, Crawford has been on his own ever since, playing major junior for four years in Moncton before turning pro. His father, Trevor, was a pretty decent player back in the day and still shares the school record at the University of Prince Edward Island for goals in a game with five. In his five years in the AHL, Crawford logged more miles on a bus than Ralph Kramden. We did the math. Crawford rode the iron lung for a total of 55,011 miles over five seasons – 12,175 and 14,898 in his two seasons with the Norfolk Admirals and 9,350, 10,385 and 8,203 in his three seasons with the Rockford IceHogs. In his rookie season in the AHL, he had a 19-day road trip that started in Bridgeport, then went to Albany, Providence, Springfield, Portland, Manchester, Hartford, back to Portland, Lowell, back to Bridgeport, then to Binghamton. Total distance travelled: 2,337 miles. Goals-against average: 3.60. Save percentage: .892. Two seven-spots and a six-goal game. Clearly, there was much to learn. Considering the circumference of the Earth is 24,902 miles, give or take a mile, that means Crawford travelled around the world twice. By bus. That’s an awful lot of watching Denis Lemieux talk about English pig dogs in Slap Shot. That’s an infinite number of card games. And it’s a Groundhog Day’s worth of trips to Milwaukee, Chicago and Peoria, home to the Carver Arena, a place where it’s so dark that sometimes the goal judge can’t even tell if the puck went in the net. But through all that, Crawford learned to be resilient. He also learned pretty quickly he was going to have to give a little on the lock ‘n’ block style that had made him a technically sound but robotic goaltender. He was going to have to become a battler, someone who never gave up on any puck. He already had the fundamental base from working with Quebec goaltending guru Francois Allaire since he was 16, but he knew he had to leverage some of his calculation in exchange for desperation. Not once, though, did he think he was being screwed, even when the Blackhawks went out and signed Cristobal Huet to a four-year deal worth $22.5 million on the first day of free agency in 2008, after Crawford had already put three years in the minors and thought he was ready for the NHL. “You wonder sometimes why you’re still there,” Crawford said. “You try to stay as positive as you can, but there were times when I thought, ‘Would I ever make it? Is this the right road for me?’ There were tons of things I thought of.” Players have a lot of time to think on those long bus rides and the long stretches between games in the AHL. Crawford used that time to build a steely resolve, one that has served him well since he stuck with the Blackhawks for good in 2010-11. Even that season,

Marty Turco was supposed to carry the load but ended up deferring to Crawford after the understudy pushed Turco out of the No. 1 spot and, with the exception of a five-game stint with the Boston Bruins the next season, out of the league. “The one thing I said to people after the year was, ‘That guy, he never had a bad day,’ ” Turco recalled. “Joel Quenneville’s practices were notorious for being goalie killers, and he really enjoyed it. He worked his tail off. And he was amazing that year.” (Two years later, when the Blackhawks won the Stanley Cup backed by Crawford, the goalie made a point of saying in his libation-fuelled speech at the parade that he and his teammates, “worked their f---in’ nuts off.” Even Barack Obama thought that one was funny, but the usually quiet and reserved Crawford will never live that one down.) There has never been any shortage of critics when it comes to Crawford. There’s a popular website among Hawks fans called www.didtheblackhawksgetashutout.com, which was established to throw barbs at Crawford and points out that from April 2011 to February 2013 the Blackhawks went 630 days without whitewashing an opponent. But with seven of his 19 career shutouts this season, Crawford is ruining all their fun. After winning his first Stanley Cup in 2013, Crawford grabbed a local television reporter and constant critic by the lapels and informed him he was aware of the criticism he was getting, but then smiled and said it was all cool because he was a Stanley Cup champion. So go ahead and disrespect Crawford and he’ll go out and prove you wrong. It might have irked him in the past, but like

Patrick Roy he puts his Stanley Cup rings in his ears these days. And things are starting to turn for him. Perhaps he’s not just the product of a superior group of defenders and some of the most diligent forwards in their own end of the ice. His play in the Stanley Cup final in 2015 was something to behold, as was his .938 save percentage. His defining moment came in Game 6 when he stopped

Steven Stamkos on a clear breakaway to seal the victory. And the accolades keep coming. Crawford played some of his best regular season hockey of his career this season and was rewarded with his first time ever on any kind of national team for Canada when he was named one of the country’s three goalies for the World Cup of Hockey. “Corey has been this good the last three or four years,” said Blackhawks GM Stan Bowman. “I don’t know why it’s taken people so long to be on board. He’s not any better than he was last year or the year before. I just think more people are starting to figure it out. Even

(Patrick) Kane has said, ‘As much as everyone talks about me, Corey has probably been our MVP this year.’ ” It’s actually quite simple. The Blackhawks need Crawford to win hockey games for them, which he does with uncanny regularity. It’s a marriage that works well because Chicago and Crawford are such a good fit. The Blackhawks know what they have in Crawford, a good first-save goalie who doesn’t move east-west very well but doesn’t have to. Former NHL goalie Steve Valiquette has emerged as one of the most respected goaltending analysts in the game, and he said during the seven-game Western Conference final last year that Anaheim goaltender

Frederik Andersen faced 23 passes through the danger zone in the slot. Crawford, by comparison, faced only four. So it becomes something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Crawford becomes a better first-shot goalie because he doesn’t have to worry much about cross-ice passes or rebounds, and the Blackhawks don’t worry about the first shot because they know they have a goaltender who can handle them. “He is one of the best at the open shot because he doesn’t have to do multiple math equations in his head for every shot,” Valiquette said. “That’s because the Blackhawks systematically cover the front of the net better than anyone else. If you were to put Corey Crawford in Edmonton, that would be the end of Corey Crawford. The work environment is such a huge factor.” At 6-foot-2 and 216 pounds, Crawford is a big man. And that, combined with his foundation in technique, made him one of those guys who put a premium on covering up as much net as possible. It works when the shooters can’t hit a pea in the top corner, but the better shooters get, the less predictable a goalie can afford to be. And he has to learn to get a battler’s mentality. Valiquette calls it the courage to step between your ears and make the tough choices and changes. “I love his battle and his compete,” Valiquette said. “He has figured it out, he’s worked for it, and he’s mentally driven through all the criticism. I’m a huge fan of what he represents in terms of mental strength.” Perhaps we should have seen this coming. After all, he was drafted in 2003, a draft that produced nine Stanley Cup winners in the first round alone. The first round, from top to bottom, is one of the strongest cohorts the league has ever produced. But as good as the first round was, the second round yielded Crawford,

Shea Weber,

Patrice Bergeron,

David Backes,

Loui Eriksson and

Jimmy Howard. (It helps there were 38 picks in the round because of compensatory picks the NHL awarded to teams who had lost free agents, a system the league has since done away with.) And even though Crawford went 52nd, he was the second goalie taken, after

Marc-Andre Fleury went first overall. As it turns out, Fleury was ready for the NHL a lot earlier than Crawford was. Because of that, he’s played almost twice as many games as Crawford, but Fleury trails in Stanley Cups and, now, recognition as an elite goalie. Fleury was named as Canada’s third goalie for Canada’s 2010 Olympic team, when Crawford was still toiling in the minors, but Fleury was not among the three named to the World Cup team. Pierre Bouchard once compared Hall of Fame teammate Ken Dryden to a duck, saying that on the surface he floats along as though everything is just fine, but what you don’t see is beneath the surface where his legs are moving like crazy. “I’d say that’s a pretty good comparison,” Crawford said. “Sometimes when you’re standing there by yourself, you start picking at yourself and overanalyzing things.” And even though Crawford has learned to temper that temptation over the years, there’s still no shortage of people who will do it for him. Which is just fine. Crawford has learned that scrutiny comes with the high profile. The national teams are a great affirmation for the great things that are going on in Chicago these days, but like so many greats like Billy Smith and Turk Broda and Grant Fuhr before him, it’s about only one thing. “I’m more worried about winning hockey games,” Crawford said, “than worrying about what people say about me.”

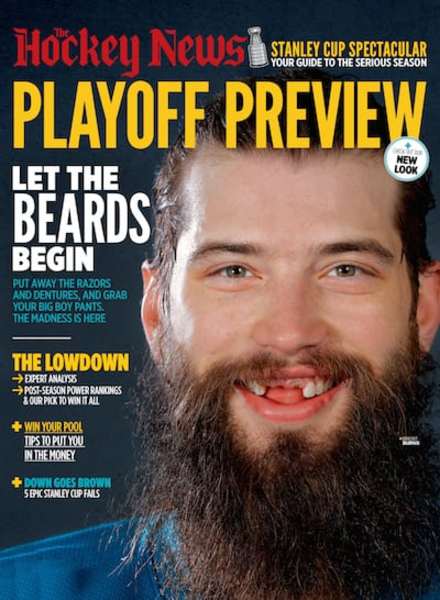

This is an edited version of a feature that appeared in the Playoff Preview edition of The Hockey News magazine. Get in-depth features like this one, and much more, by subscribing now.