How documentary 'Soul On Ice' redefines what it means to be black in hockey

What has kept black representation in hockey low throughout the years? A new documentary, Soul On Ice, aims to inform and educate on the history of black players in the sport with hopes of inspiring more to play it.

How documentary 'Soul On Ice' redefines what it means to be black in hockey

How documentary 'Soul On Ice' redefines what it means to be black in hockeyA basement full of hockey players snacking on pizza doesn’t typically make for an intense environment. But this humid August evening is an exception.

Strewn across the considerable couch space at the beautiful home of Mike Wilson, famous Toronto memorabilia collector: Joel Ward, Devante Smith-Pelly and Anthony Stewart. They represent a small chunk of the NHL’s growing black population. Also on hand: retired trailblazer Mike Marson, one of the game’s first black players. Some other NHLers, such as Mike Hoffman and Michael Latta, have tagged along, too.

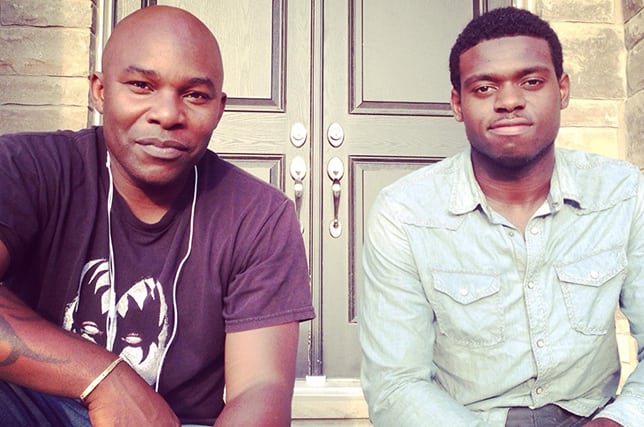

And there’s tension in the air. We all wait as intrepid documentarian Damon Kwame Mason tinkers with the audio of a giant home theatre setup. He’s about to unveil a rough cut of his labor of love, Soul On Ice: Past Present & Future, and he wants everything to be absolutely perfect. The sound system isn’t quite on point for the first few seconds of his film, and that just won’t cut it. He starts it from the top several times until he knows it’s just right.

And from the minute the opening credits of Soul On Ice arrive, bathed in edgy hip-hop, everyone in the room understands how important this screening is. Mason has spent the last several years pouring his energy into documenting the history of black players in hockey, what hardships the pioneers overcame to break into the sport and why our perception of black players in the game is changing. He’s on a mission to show that black hockey roots run deeper and longer than so many of us realize, and he wants to shatter stereotypes of what it means to be a black hockey player today.

The seeds of Mason’s project were planted in his childhood, playing road hockey on the streets of Toronto in the late 1970s. Every kid pretended to be his favorite player, and Mason loved Guy Lafleur. "No, you can’t be Lafleur," he remembers one kid telling him, because Lafleur was white.

“I wasn’t upset about it, because it’s a fact that he’s not black, you know?” Mason said. “So I had to deal with that. You grow up thinking that: ‘We don’t play hockey. This is one of the games we don’t play.’

“And that is the running joke or tease in the neighborhoods, that the ankles are too small and the arenas are too cold. But I almost didn't want to argue with anybody about it, because when you did, they would say ‘Well, who's playing in the NHL?’”

A handful of guys were at the time, including Marson and Tony McKegney. Willie O’Ree had broken the NHL color barrier in 1960-61. But it was the 1970s, when the world was less educated on these kinds of facts, and Mason didn’t have those visible role models yet. He looks back on that time now and wishes he knew more about black players as a kid.

Without understanding what the Marsons and McKegneys were accomplishing in the NHL, Mason gave in to the pressure of social norms during those awkward adolescent years when everyone just wants to fit in with the other kids. He played organized hockey a couple seasons but stopped when he began hanging out with a predominantly black group of friends at school.

“Back then, there was such a divide in everything,” Mason said. “If you were black, you listened to hip-hop, and you played basketball, and you did all the things black people did. If you started listening to heavy metal, they would call you ‘whitewashed.’ So I almost said, ‘I have to stay in this little box.’”

And so Mason kept his hockey jerseys and heavy metal albums at home for fear of being teased for liking “white” things. The divided mentality between the cultures bothered him, and it helped inspire the idea for Soul on Ice years later.

Mason moved to Edmonton in 2005 and took a job as a radio host. He knew he wanted a career in the entertainment industry. His first goal was to be an actor, but his booming voice made him an ideal on-air personality. He ended up meeting Georges Laraque, then the Oilers’ enforcer and undisputed toughest player in the NHL. Mason and Laraque teamed up for Summer Lovin’, a show in which Laraque gave romantic advice to callers. They struck up a friendship, and Mason found himself rubbing shoulders with many of the Oiler players. He enjoyed the culture and how approachable the team was compared to athletes he'd met from other sports. He couldn't help but wonder why more black players weren't playing such a great game with such a fun atmosphere.

Mason felt compelled to learn more about the history of black players. He wanted to dig up anything that could help him get his message out and let the black community know not only that they should give hockey a try, but that far more of them had done so already than many people realized. It irked him that plenty of Americans new about the Harlem Globetrotters in basketball and the Negro leagues in baseball but that Canadians had little to no knowledge of the Colored Hockey League, a circuit dating all the way back to 1895 in Nova Scotia.

“I started printing out all these articles and putting them in a folder and said, 'One day, I’m going to do a documentary about blacks in hockey,' ” he said.

By 2012, he had enough research to start making Soul on Ice.

Getting the project off the ground wasn’t easy. Mason was a first-time filmmaker – “It’s not like I was Spike Lee, he said” – yet he knew he needed the voices of prominent black players to tell his story. It helped that he had his friend Laraque to make a “sizzle reel” and show the project was legit. One by one, players began participating in the project, from the classic heroes like O’Ree, to legends like Grant Fuhr, to modern stars of the game like Wayne Simmonds.

The subject matter was delicate at times. Mason’s message was about far more than racism, as his goal was to make something that inspired positive feelings toward the game and made black players realize they belonged in the sport. At the same time, the hardships endured to date by those breaking into the NHL as black players couldn’t be ignored. He need them to tell that part of the story, too, even if it was hard to.

“As Canadians I find we always want to pretend Canada is this bastion of no racism, ‘not in Canada, it’s perfect,’” Mason said. “But the players have gone through it. So why not talk about what you've gone through so that it doesn't happen again? If people think there aren’t black kids playing hockey today that are getting cursed out because of their color alone, they are sadly mistaken. And I want people to understand that these guys have gone through it, and they’ve persevered through the adversity.

“So the lesson in this whole thing is you might be the only one, you might be called every name in the book, but that does not mean you should stop, because these guys didn’t stop and look at where they are now."

Mason even got participation from parents of players, from Simmonds to Trevor Daley, to explain how they persevered through persecution as children. In the process of researching and wrangling interviews, a happy accident occurred. Mason was attending a 2012 Toronto Marlboros game, watching a stacked team that included Connor McDavid, Josh Ho-Sang, and Sam Bennett. Mason was there to meet up with Don Cherry, who appears in Soul On Ice. Someone told him the Subbans’ parents, Karl and Maria, were in attendance and pointed them out. Mason approached, said “Hi, Mr. Subban,” and it was a case of mistaken identity. Mason was actually talking to the parents of Jaden Lindo, a young black prospect. They hit it off and, a while later, Mason had a brainstorm.

“I thought to myself, what did I want to show? And the one thing I wanted to show was a black family, mother, father and a child. I didn’t want to do a mixed family, because I felt like if I did a mixed family someone would be like, 'He’s half white.' I wanted to show a dark-skinned, black child going to play hockey. It’s more powerful in my mind, and you don’t have that question, ‘well he’s not totally black.’

“And I wanted to show you a mother and a father, because I think media-wise, when it comes to the portrayal of the black family, it’s always the single parent. I wanted to show people, hey there is the mother, the father and there’s the child, and he’s playing hockey.”

And a star was born. Mason decided to feature Lindo and his family during 2013-14, Lindo’s NHL draft year, while he went through the ups and downs of a season with the OHL’s Owen Sound Attack. Mason was drawn to Lindo’s earnest, humble attitude, and his story became a primary narrative woven throughout Soul On Ice.

“I wish when I was younger I had something like this to watch,” Lindo said. “It would have changed my thoughts, and to be featured with all the NHL players and all the history that's in the documentary, being a part of that and this film, is unbelievable for me. I am very proud and glad Kwame gave me this opportunity and chose me.”

The Lindo angle gives Soul On Ice a fresh feel alongside all the fascinating history. He represents the modern idea of the black hockey player that Mason so passionately wants to show us in hopes of encouraging more participation from the black community. And the film’s tone, featuring an urban grey palette and a hip-hop heavy soundtrack, hearkens to Mason’s adolescent identity crisis. He wants to blur the lines between pieces of culture defined as “black” or “white.” He says he’s always felt hip-hop synced up with hockey footage just as well as it did with basketball footage. So why not try it and tell viewers right away they’re experiencing a different kind of documentary?

“The generation now doesn’t see it like us older people,” Mason said. “They don’t put us in these boxes. These kids now are in the dressing rooms playing hip-hop music.”

Back to the basement, where the sneak preview has just finished screening. Mason breathes a sigh of relief. A roomful of athletes rises and lines up eagerly to shake his hand. They’re blown away by the bold piece of filmmaking they’ve just seen.

“It was a great movie,” Stewart said. “I feel sense of pride. It was done really tastefully. I think the overall message was that hockey is for everyone, and if you can change one kid’s mind from having second thoughts about playing hockey… when they see the past, present and future of black hockey, it’s motivation for them to play the game. The documentary has done its job.”

Soul On Ice premiered at the Edmonton Film festival Oct 7. It arrives in Toronto next week for a private screening, with a public screening expected in the coming weeks as well. For more information, and to contact Mason about seeing the film, visit the official website here.

“It’s an unbelievable story, and it’s good that someone is telling it,” Ward said. “Hopefully it gets positive feedback.”

Matt Larkin is an associate editor at The Hockey News and a regular contributor to the thn.com Post-To-Post blog. For more great profiles, news and views from the world of hockey, subscribe to The Hockey News magazine. Follow Matt Larkin on Twitter at @THNMattLarkin