Skating on thin ice: How climate change could hurt hockey's future

Climate change is slowly killing the game played in the great outdoors. A movement is afoot to change that.

Skating on thin ice: How climate change could hurt hockey's future

Skating on thin ice: How climate change could hurt hockey's futureHockey is entering a new ice age, and how the community deals with it could have a significant bearing on the evolution of the game. Climate change may not affect where we can put an indoor rink, even in the warmest climes, but it’s having a profound impact outdoors, where the game was born and its mystique still lies.

Today, Torontonians get about 60 days of outdoor skating a year. So do those in Montreal. That’s two months to play keep away with your siblings, pretending to be various members of the Staal family out on a sod farm in Thunder Bay. Or maybe you and your buddy are John Tavares and Sam Gagner, who used to skate in Gagner’s backyard so often the pizza delivery guy knew to bypass the house and head straight to the homemade rink. Either way, play hard now, because those days are dwindling.

This shouldn’t come as a newsflash. In 2012, members of McGill University’s department of atmospheric and oceanic sciences proved the skating season in Canada was shrinking. Fifty-five years prior, you’d have had upwards of 15 more days of outdoor shinny. But those days are getting fewer as we continue to burn fossil fuels. Will hockey have to sacrifice the outdoor game for the indoor one?

Robert McLeman, associate professor of geography and environmental studies at Wilfred Laurier University in Waterloo, Ont., compares the precarious nature of the outdoor rink to polar bears. “Scientists will say, ‘Well, polar bears are going to disappear,’ but people won’t see polar bears unless they go to a zoo, so there’s no personal connection to the impacts,” he said. “But when you say, ‘Well, you won’t be able to build a rink in about 20 years time,’ they’ll say, ‘What? Hold on a second. We love skating!’ And so suddenly there’s this personal connection with what’s going on.” McLeman is working on an upcoming study showing that by 2090 the number of skating days in Toronto will fall by a third. That means those dream teams created in neighborhood rinks will only have 40 days of outdoor ice time. The same goes for those in Montreal, which will experience the same sharp 33 percent decrease, and Calgary, which will lose 20 percent of skateable days. Consensus among the scientific community is that climate change is affecting backyards all along the Canadian-American border. To prove this, McLeman helped launch a data collection survey, RinkWatch, which allows backyard flooders to pinpoint their homemade rink’s location on a map and report their skating conditions throughout the winter. The web-based citizen-science program allows McLeman and his team to chart winter weather across North America, determine temperature thresholds that yield the best ice conditions and predict the number of skating days in the future. Recorded data on RinkWatch guarantees a skateable rink at temperatures lower than 14 degrees Fahrenheit, but a few degrees warmer and the quality of the ice rapidly declines. At 23 degrees Fahrenheit, there’s only a 50 percent chance of the ice being skateable, according to McLeman. To put it into perspective, a typical year in Boston yields 36 days colder than 23 degrees, allowing for a 50-percent chance of good skating. But a one-degree warming in the average temperature in Boston – which McLeman believes can be expected in the coming decade – will shrink those days down to 17. “There comes a point where you ask yourself, is it even worthwhile building an outdoor rink?” he said.

The paradox between performance and sustainability is becoming increasingly important, and few understand this better than three-time U.S. Olympian and former New York Rangers goaltender Mike Richter. Since retiring in 2003, Richter has received a degree in ethics, politics and economics from Yale University and serves on many environmental committees, including the Sierra Club. “I’ve heard for years, ‘This’ll be an issue for our grandchildren,’ ” he said. “No, it’s an issue now. It will be a profoundly disturbing issue for them unless we address it now.” Richter, who in 2011 founded Healthy Planet Partners, a company that retrofits commercial buildings with a clean energy supply, believes there’s a natural alliance between athletes and the environment and that athletes are in a privileged position to raise awareness concerning sustainability. “Every method that you can use to address the issue of these environmental effects needs to be used,” he said. “And by that I mean you need charity, volunteers, NGOs, capital markets – everything – because these problems are so big. They’re so difficult to handle.” In this way, the NHL has been a leader. In 2008, the league partnered with the National Resource Defense Council to provide each team with a “greening advisor” who serves as a guide to promote ecological practices in their hometown arenas. In 2011, at the Winter Classic held at Boston’s Fenway Park, commissioner Gary Bettman unveiled NHL Green, the league’s environmentally conscious and socially progressive program that united individual teams’ efforts under the power of the official seal. According to the league’s website, NHL Green has five goals: track impacts; reduce energy, waste and water; offset impacts; support environmental programs; and inspire environmental progress. Examples are initiatives like Gallons for Goals and Rock and Wrap It Up, programs that recycle water and food waste created on game days. In 2014, NHL Green did something no pro sports organization in North America had done yet. It published a sustainability report upon collecting its own data, coming clean of its 530,000-metric-ton carbon footprint and all the ways it was striving toward more environmentally friendly operations. In 2015, it became the first pro sports league to achieve a spot on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Top 100 list of the largest users of green power. According to the sustainability report, nearly all league facilities have adopted more efficient lighting, which has proved a significant return on investment. From there, individual venues have addressed specific needs, ranging from revamped humidity control, the elimination of harmful refrigerants and retrofitting cooling technology to make ice and arena maintenance more environmentally sustainable. For Richter, the key to reducing our environmental impact has everything to do with efficiency. He said that when you’re producing a lot of waste, it means your operations are working more than they need to be. “That’s the lens with which we need to start viewing these environmental problems,” he said. “Is there a more efficient transportation of the public or private? Can you put solar on the roof instead of using electricity from a coal plant? There are a lot of technologies that work – that’s what I do in my job right now – but to have a forum like the league is increasingly creating a very powerful thing, because the technology’s out there, the money’s out there, but I think the awareness of it is the one thing that’s lacking.” Richter lauds current NHLers involved with NHL Green initiatives who can find the time to play and preserve. Edmonton Oilers veteran defenseman Andrew Ference, who is currently enrolled at Harvard working toward a certificate in sustainability and innovation, is a popular spokesman. “There’s definitely been a bit of a revolution over the last few years with the big venues, the venues that have capital to make the investments in the more sustainable technology and the more efficient technology,” Ference said. “Rinks are becoming more and more energy efficient every single year. But you still see all of these community rinks – the one that I skate at over the summer – they’re very inefficient.” There are 2,631 indoor hockey rinks in Canada, the majority of which are probably closer to Ference’s summer slab than Rexall Place. While engineering companies are beginning to understand that many of these family owned and operated rinks don’t have the kind of capital to retrofit, there are smaller, more fiscally responsible technologies beginning to develop. For example, RealIce, a Vancouver-based company, manufactures an easy-install device akin to a pipe, 100-percent maintenance free and with no other energy sources necessary. Water flows through the device at such speed that a vortex is created, removing majority of the micro-air bubbles. The water – which is never heated, saving energy – is then used to resurface the ice. The de-aeration process makes for a smoother, harder ice that has a positive ripple effect on the other processes in the arena, such as lowering the draw on compressors and boilers, the amount of water used and wasted and overall energy consumed. The company’s return on investment is two to three years for a single pad rink, and one to two years for a twin pad. The NHL has become a familiar face with technological innovations that lower utility costs and help the environment. The league has utilized RealIce in the construction of its outdoor rinks for the Winter Classic, Heritage Classic and Stadium Series games since 2010. The NHL has also caught wind of RinkWatch and advertises the program on the NHL Green’s website. “They recognize that part of hockey is the shinny experience, the backyard skating experience, and when – or if – that were to disappear, it sort of goes right to the roots, the tradition of hockey,” McLeman said. “Wayne Gretzky in his dad’s backyard, Bobby Hull playing on a frozen pond out in the prairies when he was a kid. You take that away and suddenly the mystique of hockey starts to erode.”

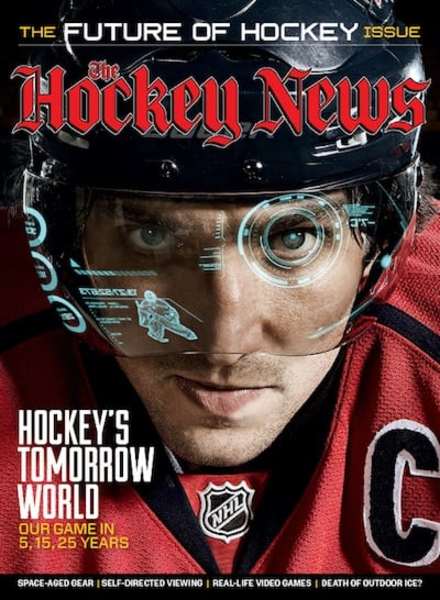

This is an edited version of a feature that appeared in the September 14 edition of The Hockey News magazine. Get in-depth features like this one, and much more, by subscribing now.