As a practice goalie with the Montreal Canadiens in the late 1950s, Gerald Wasserman put his life on the line every time he saw Bernie 'Boom Boom' Geoffrion coming down the wing and winding up for a slap shot.

The puck frequently went in the net, as you would expect from a sniper like Geoffrion, but it whizzed past Wasserman’s head often enough that the young goalie soon decided life in the sometimes-cutthroat world of corporate Canada would be much safer. And, interestingly, that’s where he ended up making his biggest saves.

Wasserman, as president and chief executive officer of Canstar Sports Inc., was the driving force behind a successful bid to buy the assets of Cooper Canada from Charan Industries in 1989 and incorporate them into the Canstar operation. One of those assets, of course, was the hockey stick factory in Hespeler, Ontario, that continues today as Roustan Sports Ltd., still manufacturing high-quality made-in-Canada wooden sticks.

Canstar Sports was only one entry on Wasserman’s lengthy resume in a career that lasted more than 40 years before he passed away in April 2005 at a relatively young age, three days shy of his 68th birthday. But according to his son, it was probably the highlight.

“He loved that company,” Robert Wasserman said in an interview, reflecting on his father’s time with Canstar. “He loved what they did.”

As head of Canstar Sports, former Montreal Canadiens practice goalie Gerald Wasserman donned Cooper pads and wielded a Hespeler-made Bauer stick for his own Fleer hockey card in 1993. (Courtesy of Robert Wasserman.)

As head of Canstar Sports, former Montreal Canadiens practice goalie Gerald Wasserman donned Cooper pads and wielded a Hespeler-made Bauer stick for his own Fleer hockey card in 1993. (Courtesy of Robert Wasserman.)Gerry Wasserman was born on April 23, 1937, in Montreal and spent most of his life in that city. The son of Jewish immigrants from Romania and Austria, he attended high school at the now-defunct Strathcona Academy and graduated from McGill University with a Bachelor of Commerce degree in 1958. After further studies at McGill and at what is now known as HEC Montreal, he earned his Chartered Accountancy designation in 1960.

He was also a netminder on McGill’s varsity hockey team, having developed a love for the game as a child. It was in this capacity that he was invited to be a practice goalie with the Canadiens.

“It was the old six-team league,” he said of the NHL in a 1997 interview with the Montreal Gazette, “and in those days, teams only carried one goalie. So the home team had to provide a standby goalie for the visiting team.” He was paid $10 to sit in the stands at the Forum during Habs’ home games, which was a good deal compared to the $3.50 he was paid to attend practices and face down howitzers from Boom Boom Geoffrion.

The Gazette reporter asked Wasserman if he ever made it into a game.

“Are you kidding?” he replied. “You would have had to catch me first.” (1)

Robert Wasserman said he was told of one occasion when a Detroit Red Wings goalie was injured during a game, and a terrified Gerry was almost called upon to play. After a lengthy delay, the unidentified goalie was able to continue, much to Gerry’s relief.

After graduating from McGill and starting his career in business, Wasserman left hockey behind, but his son said it was never far from his heart.

“Every little boy in Montreal was starstruck by hockey,” Robert said. Indeed, the 1997 Gazette article noted above included a photograph of Gerry posing with the skates and Canadiens sweater that he had worn as a young man. He had kept them all those years.

Wasserman was a fast mover in the corporate world, excelling first in the retail and wholesale food industry. An executive position with the Steinberg’s chain led to his appointment as a vice-president of administration and finance with rival chain Spot Supermarkets in 1966, while he was still in his 20s. Two years later, Wasserman jumped to the Marché Union chain as its vice-president of finance. From there, he went to Belanger-Tappan Inc., which manufactured household appliances, as an executive vice-president and member of the board of directors. Mentored by company chairman Yvon Simard, Wasserman became the president of Belanger-Tappan in 1974. (2)

Stepping into a different industry also led Wasserman to the chairmanship of the Canadian Appliance Manufacturers Association by the end of the decade. (3) With the new decade, however, came a new role in another new industry, as president and chief executive officer of Melcan Distillers Ltd. (4)

Melcan, a holding company based in Montreal, was owned by a consortium of distillers and was eventually taken over by Distillers Corporation-Seagram Ltd., the global liquor powerhouse formerly known as Joseph E. Seagram and Sons – remember them from our previous chapters? It can be assumed that running Melcan would have brought Gerry Wasserman into close contact with the Bronfman family for the first time.

Ed Seagram had taken Seagram’s public in 1926 – Canada Barrels and Kegs was not part of that process – and the Bronfmans, under the direction of family patriarch Samuel Bronfman, won control in 1928. Cemp Investments Ltd. was established as a private trust for Sam Bronfman’s four children: Charles, Edgar, Minda and Phyllis; their first initials gave Cemp its name. In 1973, Cemp took over a firm called Warrington Products, which produced and distributed various consumer goods. (5)

Its original focus appears to have been on “waterproof products,” according to the Montreal Gazette. “But it discontinued that unprofitable business by 1973 and proceeded to embark on a buying spree of a dizzying array of ventures.”

There was little consistency in these ventures, which ranged from plastic pipe making to household appliances, luggage, women’s footwear and more. (6) One of its purchases, in 1974, was Greb Industries Ltd. of Kitchener, which manufactured Hush Puppies shoes, Kodiak boots and Bauer skates. This acquisition gave Warrington a toehold in the Canadian sporting goods industry. (7)

Warrington’s annual sales skyrocketed by nearly 900 percent in a little more than a decade, but its losses also increased at a similarly rapid rate, and by 1988 it had debts valued at more than $90 million and a negative net worth of more than $30 million.

“It had all kinds of sales but never had any profits,” Gerry Wasserman said in 1990. “The company was for all intents and purposes insolvent.” (8)

Several years earlier, Warrington had acquired an Italian ski boot and skate manufacturer. As part of that deal, the company’s founder, Icaro Olivieri, was invited to join Warrington’s board of directors, and soon after that, Olivieri became president of Warrington. (9)

His skates, which were marketed under the brand name Micron, were sold alongside Bauer and Lange, two other brands Warrington had acquired. Their combined sales performance was strong enough that when Warrington sold off most of its Greb assets in March 1987, including Hush Puppies shoes and Kodiak boots, it kept the skate companies. (10)

But there was trouble in the executive suites as Olivieri watched Warrington move closer to the brink of bankruptcy while Cemp tried to sideline him from the company’s operations. A power struggle ensued, and Olivieri teamed up with DCC Equities, a merchant bank owned by mutual fund manager Dynamic Capital Corporation, to buy out Cemp for $8.9 million and take control. Olivieri became chairman of Warrington. Wasserman, who by this time had earned a reputation as a “turnaround” expert with a knack for reviving struggling businesses, took a five percent ownership share and was put in charge of reorganizing the company. (11)

Prior to this, he had switched industries yet again and was working for Astral Bellevue Pathé. Little is known now about Wasserman’s time with that media company, which produced the raunchy comedy movie Porky’s and pioneered “Pay TV” in Canada through its establishment and ownership of the First Choice premium channel (later The Movie Network, now known as Crave).

Robert Wasserman believes his father succeeded in so many different fields because of his open enthusiasm for everything he did.

“He was a colorful guy – gregarious, outgoing,” Robert said. “He enjoyed things, and he enjoyed people.

“He really engendered a lot of loyalty from people who worked with him. And he had a really high standard for excellence.”

And so, Gerry Wasserman found himself back in the world of hockey nearly 30 years after he had left it behind.

One of his first moves was to change Warrington’s name – Canstar Sports had been the name of its sports subsidiary, and now Canstar Sports Inc. would be the company’s official identity.

As president and CEO, Wasserman decided the company would concentrate on skates and jettison its unprofitable sectors, including the ski equipment division that had brought company chairman Icaro Olivieri to Canada in the first place. All three skate brands – Bauer, Lange and Micron – were strong, so they were all retained.

But while Wasserman was focused on the reorganization of Canstar, he couldn’t have helped but notice the plight of another troubled Canadian sporting goods company.

Charan Industries had bought Cooper Canada in 1987 from Jack Cooper, but it turned out to be a disastrous move, and Charan was soon hemorrhaging money. Charan had made its name as a toy importer and distributor, but unfortunately, it knew little about manufacturing, and it knew nothing about producing unfamiliar items like hockey sticks, helmets, gloves and shoulder pads. Its efforts to meet the continuing strong demand for Cooper gear were costly and inefficient. (12)

“With Cooper, we thought we were buying expertise in manufacturing,” Charan president and chief operating officer Earl Takefman said in 1989. “Then we found out that manufacturing was actually one of Cooper’s problem areas, and we didn’t have the expertise to dig ourselves out of the hole.” (13)

It’s doubtful that manufacturing was really the issue, because it had never been a problem before. Wasserman likely became aware that management was the real problem and, recognizing the value of the Cooper assets, he pondered the idea of purchasing them from Charan.

“The last thing we needed was to buy another company,” he said in 1993. But he reasoned that Cooper was a perfect fit for Canstar Sports because of its solid reputation in producing protective hockey equipment and, thanks to its ownership of Hespeler St. Marys Wood Specialties, its growing knowledge of hockey stick production.

Wasserman decided to go ahead, spending $30.4 million to bring Cooper’s hockey line into the Canstar Sports fold. (14)

That was about $6 million less than Charan had spent to buy Cooper only two years earlier, a deal that Takefman regretfully called “my Waterloo” in reference to the famous Battle of Waterloo, apparently casting himself as the ill-fated Napoleon Bonaparte. (15) (He probably would not have appreciated knowing that Waterloo Region, the home of Cooper’s hockey stick factory in Hespeler, had been named in honor of that battle.)

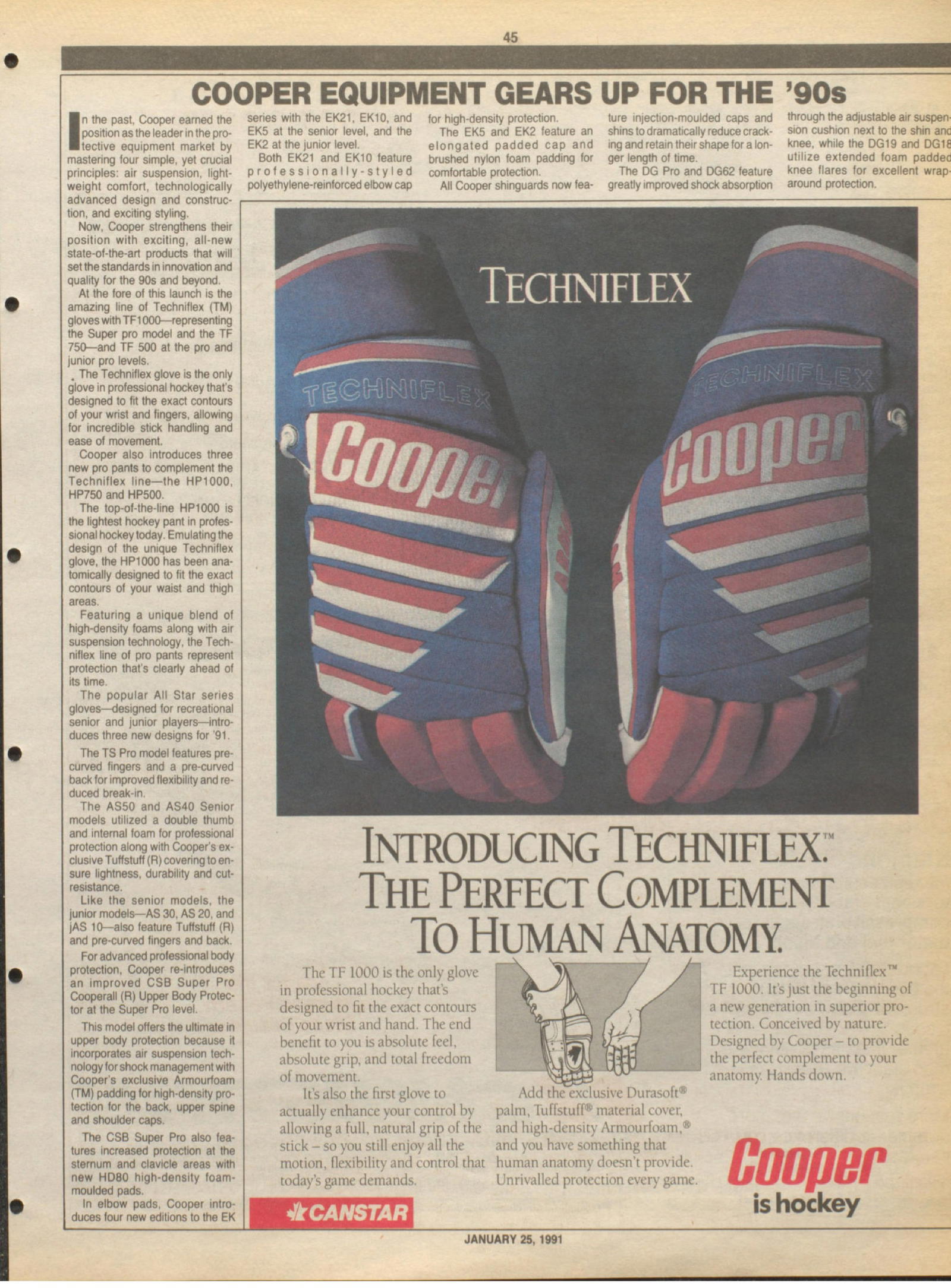

A Cooper article and advertisement (with the Canstar logo) appeared in a January 25, 1991, edition of The Hockey News.

A Cooper article and advertisement (with the Canstar logo) appeared in a January 25, 1991, edition of The Hockey News.Giving up on Cooper also spelled the end of the business relationship between Charan’s founding partners, with Takefman resigning on the completion of the sale to Canstar. (16) Chairman and CEO Sol Zuckerman did indeed blame Charan’s day-to-day management or, in his opinion, its mismanagement.

“We had nobody controlling the growth of the company,” he said, in a clear shot at Takefman. “You’ve got to have controls or otherwise dollars don’t go through the cracks but through the windows.” (17)

Charan never recovered and soon disappeared from the Canadian corporate landscape. Takefman and Zuckerman separately returned to the hockey industry but fared no better the second time around.

Zuckerman was the co-owner of a Florida franchise in Roller Hockey International, a short-lived professional inline hockey league. Takefman’s second failed hockey venture coincidentally led to another intervention and successful save by Gerry Wasserman – more on that in a subsequent chapter.

In the meantime, though, Wasserman was flying high after completing the Cooper deal. He wasn’t worried about the possibility of repeating Warrington’s flawed strategy of buying companies simply for the sake of buying them. Nor was he worried that the acquisition of the Cooper hockey assets would take a bad turn as it had for Charan.

It was “a natural fit” for Canstar, he said. “We’re in the hockey business, and Charan wasn’t.” (18)

“In the hockey business” was an understatement. In March 1990, Canstar’s various skate brands could reportedly be found on the feet of 70 percent of NHL players. The company was producing 1.3 million pairs of skates annually. And Wasserman was quickly vindicated in his decision to expand Canstar while simultaneously reorganizing it.

“Once mired in red ink, it has enjoyed seven quarters of profits,” a reporter wrote in the Montreal Gazette. “Sales this year are expected to skyrocket to more than $140 million from about $90 million in 1989 because of the Cooper purchase.” (19)

By May, Wasserman was able to report that although Canstar had posted a loss in the first quarter due to costs related to the Cooper purchase, the shortfall “was much less than we expected,” and Canstar was on track for another profitable year. The sales outlook continued to be positive and, as Wasserman told the Gazette, Canstar’s general financial position was “the strongest it has been in many years.” (20)

Whatever problems Cooper may have encountered in the manufacturing process under Charan did not appear to be significant factors under new ownership and management, a strong suggestion that they never were significant factors in the first place.

Jack Cooper, the founder of Cooper Canada, had tried to buy CCM for its skate production because he wanted to fulfill his dream that hockey players would wear his products from head to toe, fulfilling the old company motto that “The world plays hockey with Cooper.”

He came close when he settled for purchasing Roos skates, but he didn’t quite make it because he didn’t control Roos’ blade production – only the manufacturing of the boots. He even hired Don Bauer, son of the founder of Bauer skates, as a consultant to be involved in design and development. It was an inspired but ultimately unsuccessful move to try to claim that Cooper and Bauer were working together under the same roof.

But now, thanks to a goalie-turned-corporate mover and shaker named Gerry Wasserman, Cooper and Bauer were finally part of the same operation, and the world would indeed be able to play hockey entirely with the gear made entirely by one Canadian company. That company would be Canstar Sports. Its story continues in the next chapter.

Jonathon Jackson is a hockey historian based in Guelph, Ontario.

Follow along as we post new chapters of Hockey's Oldest Business – Since 1847 on TheHockeyNews.com.

Read the previous chapter: Chapter 8 – Cooper Canada

Read the previous chapter: Chapter 10 – Canstar Sports 2

(1) François Shalom, “CCM is back in the game,” Montreal Gazette, February 17, 1997.

(2) “Spot Supermarkets Appointment,” Montreal Gazette, February 16, 1966; “Marche Union Inc.,” Montreal Star, November 5, 1968; “Belanger-Tappan Inc.,” Montreal Gazette, June 12, 1974.

(3) “Energuide labels the way to appliance energy use,” Montreal Gazette, May 10, 1979.

(4) “Melcan Distillers Limited Appointment,” Montreal Gazette, July 16, 1980.

(5) “Cemp buys Warrington shares,” Toronto Star, October 9, 1973.

(6) Craig Toomey, “Canstar sharpens its blades,” Montreal Gazette, March 10, 1990.

(7) Henry Koch, “$11.1 million is offered for Greb Industries Ltd.,” Kitchener-Waterloo Record, May 1, 1974.

(8) Ibid.

(9) “Brascan mum on plans for Scott,” Montreal Gazette, January 10, 1981; “4th quarter weak, Warrington makes $746,000 profit,” Kitchener-Waterloo Record, July 3, 1982.

(10) “Warrington plans move to end losses,” Kitchener-Waterloo Record, June 3, 1988.

(11) “Chairman fights to regain voice in Warrington,” Montreal Gazette, Feburary 20, 1988; “Warrington’s major shareholder acquires control of firm with DCC,” Montreal Gazette, July 1, 1988; Mark Evans, “Canstar Sport skates back to top of hockey equipment heap,” Financial Post, September 25, 1990; Craig Toomey, “Canstar sharpens its blades.”

(12) Mark Evans, “Playing field is rocky for sports equipment makers,” Financial Post, April 17, 1989.

(13) Jay Bryan, “Takefman accepts blame for problems at Charan,” Montreal Gazette, December 7, 1989.

(14) John Greenwood, “He Shoots He Scores,” Financial Post Magazine, June 30, 1993.

(15) Jay Bryan, “Takefman accepts blame.”

(16) Philip DeMont, “Cooper hockey assets to be sold,” Toronto Star, December 2, 1989; “Cooper’s hockey assets completely bought out by Canstar Sports Inc.,” Kitchener-Waterloo Record, December 2, 1989.

(17) Mark Evans, “Charan returns to roots,” Financial Post, February 3, 1990.

(18) Craig Toomey, “Canstar sharpens its blades.”

(19) Craig Toomey, “Canstar sharpens its blades.”

(20) “Loss less than expected, Canstar says,” Montreal Gazette, May 26, 1990.