The next chapter in the made-in-Canada story of Roustan Sports Ltd. takes us to St. Marys, Ontario, a town situated on the Thames River, near Stratford in Perth County.

Home of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, St. Marys – no apostrophe – is also the hometown of Canadian sportswriting legend Milt Dunnell, for whom a local park has been named.

Not surprisingly, there is a rich hockey history here as well.

Dan McCarthy, who managed to score four goals during a brief National Hockey League career that lasted only five games in November 1980, is from St. Marys. So is Sam Sedley, who recently entered the OHL record book as the top scoring defenseman in Owen Sound Attack franchise history.

And the St. Marys Lincolns have represented the town in Ontario Hockey Association Jr. B ranks continuously since 1956; Terry Crisp, J.P. Parise, Don Luce, Jack Valiquette, Dan Bylsma, Bob Boughner, Scott Driscoll, Steve Miller, Steve Shields and Matt Read are a few of the Lincolns who eventually made it to the NHL as players or as on-ice officials.

St. Marys is known as 'Stonetown' due to an abundance of limestone deposits in the area that provided building material for many homes and other structures in town that still stand, including the town hall and two iconic railway trestles. It is said that limestone from St. Marys was used in the construction of Maple Leaf Gardens, and limestone is still used today in local cement production. But the lumber industry was also prominent in St. Marys, and it was this interest that brought Solon Lewis Doolittle to town just after the turn of the 20th century.

Born in 1854 near Aylmer in Elgin County, Doolittle had a long history of working with wood, starting with cabinet making and then manufacturing furniture in Berlin (now Kitchener). But he wasn’t content to just build – he wanted to create new things as well. It was while working for D. Hibner and Company in Berlin in the late 1880s that Doolittle applied for and received two patents with Daniel Hibner, the factory owner.

In 1894, Doolittle left Hibner’s employ and entered a partnership with the Ellis Furniture Company of Ingersoll, near London, but six years later he sold out and returned to Berlin to head up a new enterprise. He convinced the town council to grant him the $1,200 purchase price of a lot on which he agreed to build a four-storey factory. (1)

The factory was called the Berlin Furniture Company and Doolittle took an active role as its superintendent, but the venture turned out badly for him. In June 1906, he suffered an accident while operating a saw, and it cost him four fingers on his left hand. Insult was added to injury when he sued the company for negligence and a jury ruled against him, attributing the fault to him alone. (2) Doolittle left the company and left Berlin, going to Montreal to work for Henry Morgan and Company. (3) But ultimately, he couldn’t stay away from woodworking. In 1908, he turned up in St. Marys, where an industrial area had developed in the south end of town.

Although Doolittle was already past 50 years of age, not to mention handicapped by the loss of most of the digits on one of his hands, he was still ambitious and industrious. He gave up on furniture and set about establishing a factory in St. Marys to manufacture handles, hockey sticks and baseball bats.

Undated photo of the factory at St. Marys Wood Specialties. (St. Marys Wood Specialty Company. Reg Near Postcard Collection, St. Marys Museum & Archives, RN6_164)

Undated photo of the factory at St. Marys Wood Specialties. (St. Marys Wood Specialty Company. Reg Near Postcard Collection, St. Marys Museum & Archives, RN6_164)The St. Marys Wood Specialty Company was incorporated in the spring of 1908 with a valuation of $40,000. (4) It opened that year in a plant on James Street South, near an established flax mill and alongside railway branch lines that carried Grand Trunk (later Canadian National) and Canadian Pacific trains to main line connections in London and Ingersoll. The CPR even built a spur line right to the factory, helping the business to ship its products “in large quantities to all parts of Canada,” one example being “six carloads of hockey sticks for Winnipeg parties.” (5)

Within a few years, the factory was churning out 16 types of hockey sticks and 27 models of baseball bats, as well as handles for axes, hammers, and picks. The town’s favorable railway connections contributed heavily to Doolittle’s success, enabling his products to be carried in large numbers nationwide.

By 1910, according to information from the St. Marys Museum, sticks from St. Marys could be found as far away as Regina. Bats were sold in places like Winnipeg, Ottawa, Montreal and Saint John, New Brunswick. Newspaper advertisements show that Doolittle had penetrated the American market by no later than 1911 and immediately developed a good reputation, with a store in Springfield, Massachusetts proclaiming “St. Mary Celebrated Hockey Sticks” to be “The best in the world” in January of that year. Twelve months later, a store in Cleveland called them “the famous St. Mary’s Canadian Hockey Sticks.” (6)

Not content with what he had already achieved, Doolittle tinkered with his designs, obtaining another patent in 1912 for a new kind of hockey stick.

His innovation was certainly unique – his idea was to place a “rib” along the lower edge of the stick blade.

“When the blade strikes the puck it will have a greater lifting power thereon increasing the accuracy of the shot,” he wrote in his patent application, adding that while his drawing only showed the rib on one side of the blade, it would be simple enough to form it on both sides “if desired.” This idea would have been revolutionary, coming decades before curved blades created actual left- and right-handed sticks for players.

It’s not known if Doolittle actually manufactured the ribbed stick; if so, the idea must not have caught on with dealers and customers. It’s more likely that he simply didn’t pursue it.

He probably had enough on his plate in 1912 with re-establishing his business after a fire in January of that year destroyed his factory – the hazards of working with lumber were very real, as the Salyerds in Preston had already learned by this point and would later experience again. But, like them, Doolittle carried on. He moved to the nearby flax mill and was soon operating again. (7)

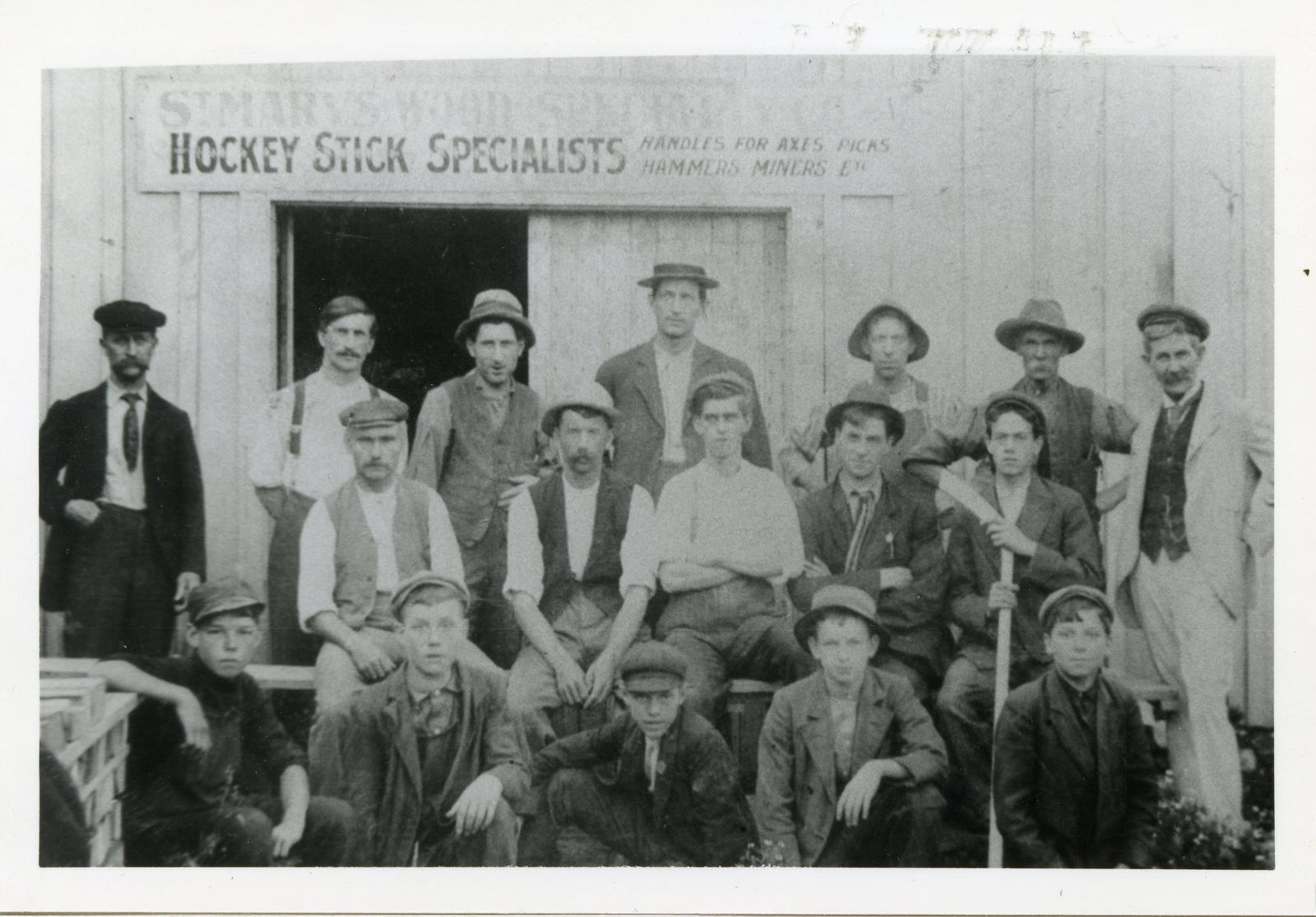

Undated photo of factory workers at St. Marys Wood Specialties. Owner Solon Lewis Doolittle is the man on the far right in the back row. (St. Marys Wood Specialty Company. Eedy Collection, St. Marys Museum & Archives, eedy007)

Undated photo of factory workers at St. Marys Wood Specialties. Owner Solon Lewis Doolittle is the man on the far right in the back row. (St. Marys Wood Specialty Company. Eedy Collection, St. Marys Museum & Archives, eedy007)Business recovered fully and, by 1917, it was claimed that St. Marys Wood Specialty was the largest hockey stick-manufacturing plant in Canada. Stores as far away as Spokane, Washington, sold St. Marys sticks to curious newcomers to hockey. One newspaper advertisement shows they were being sold for $1.25, reflecting their quality; so-called “amateur” sticks from other, unidentified manufacturers cost only 35 cents at the same store. (8)

Doolittle died suddenly in October 1919 at age 65, but the company continued to prosper under managing director Neil Currie, who had previously worked as an engineer before coming to St. Marys either with Doolittle or shortly thereafter. Currie obtained a patent for a three-piece goalie stick in 1922, and the company also developed a stick with a pinned blade.

Newspaper advertisements from the era show St. Marys sticks for sale in more American cities, such as Boston and Minneapolis. (9) A sporting goods store in Bridgeport, Connecticut listed eight different models for sale in the winter of 1922, ranging in price from 50 cents (the “Boys Expert”) all the way to $2.00 (the “3 Piece Goal” stick). The other models were the Amateur, Reliance Forward, Reliance Defence, Hand-Made Forward, Hand-Made Defence, and Regular Goal. (10)

Times were good for the company, which treated its employees fairly and saw that treatment reflected in their loyalty. One man, Russell 'Buster' Seaton, reportedly worked for the company for 55 years, and some of his sons and grandsons were also employed there. Seaton’s presence loomed so large among his coworkers that even after he passed away, his son Charles was still being called 'Young Buster' even though he was 57 years old and had been working for the company since he was 16. (11)

Old Buster had started his career in St. Marys, but he did not remain at the factory there, nor did anyone else. Currie retired soon after obtaining his patent and died in December 1928. The Great Depression began the following year, and St. Marys Wood Specialty, like so many other Canadian businesses, found it difficult to survive.

In July 1933, it was revealed that the company had been acquired by parties “which will amalgamate the business there with the Hespeler Wood Specialty Co., Ltd., makers of hockey sticks, and with two other hockey stick factories at present located at Preston and Ayr.” (12)

The article, published in the Brantford Expositor, didn’t identify the parties in question, but we know now they were the Seagram family. Operating under the name Waterloo Wood Products, they had bought E.B. Salyerds and Sons of Preston in 1929 and had taken full control of it in 1932, also absorbing Ayr’s Hilborn Company along the way.

After the Seagrams bought the St. Marys plant, they allowed work to wind down, and there was a lot of it – the Kingston Whig-Standard reported in August 1933 that the factory was working around the clock to fulfill axe handle orders that had been placed from as far away as Australia. (13)

The closure was inevitable, though, and it happened in November 1933, with the employees and machinery being transferred to Hespeler. Harry James, who had been managing the factory since Currie’s death, was specifically kept on as manager of the combined operation.

Undated photo of the factory in St. Marys. (St. Marys Wood Specialty Company. Reg Near Postcard Collection, St. Marys Museum & Archives, RN6_164)

Undated photo of the factory in St. Marys. (St. Marys Wood Specialty Company. Reg Near Postcard Collection, St. Marys Museum & Archives, RN6_164)The Stratford Beacon-Herald lamented the end of the factory in an editorial that was republished in the Kitchener newspaper, pointing out that although the merger was probably good business, it didn’t properly account for what was being left behind.

“We admit it is always possible to make out a good case for a move of that sort; everything about it can be made to appear reasonable and right,” the editorial said. “And yet the result is always the same. Four plants have gone into the merger at Hespeler. It will mean one busy place there and a closed factory in St. Marys, another one in Preston, and another in Ayr.” (14)

Nothing took the place of stick manufacturing at the St. Marys factory, which was later demolished. Fast food restaurants now occupy the site, which is across from the local high school. But there are still some reminders of St. Marys Wood Specialty’s presence. The CN rail line that serviced it and other nearby industries is still there, although the CP line was torn up decades ago. A heritage plaque was designed a few years ago to commemorate the plant and its important history.

The hockey stick company left St. Marys behind but took the town’s name with it. Waterloo Wood Products completed its buying and consolidation spree with this move and changed its corporate identity in 1935. For the next four decades, the company would be known as Hespeler St. Marys Wood Specialties. It would also continue to manufacture baseball bats under the familiar St. Marys brand, reinforcing an important link to the past that Roustan Sports Ltd. is proud to acknowledge.

Jonathon Jackson is a hockey historian based in Guelph, Ontario.

Follow along as we post new chapters of Hockey's Oldest Business – Since 1847 on TheHockeyNews.com.

Read the previous chapter: Chapter 2 – Preston

Read the next chapter: Chapter 4 – Hespeler

(1) “Going to Ingersoll,” Berlin Daily Record, April 9, 1894; “A Busy and Important Session,” Berlin Daily Record, March 6, 1900.

(2) “Around Town,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, June 9, 1906; “Company Was Not Negligent,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, October 27, 1906.

(3) “Going to Montreal,” Berlin Daily Record, July 25, 1906.

(4) “Ontario Gazette,” Ottawa Citizen, April 27, 1908.

(5) “News of Railroads,” Montreal Gazette, March 23, 1910.

(6) Harry L. Hawes advertisement, Springfield Evening Union, January 31, 1911; The Collister & Sayle Co. advertisement, Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 12, 1912.

(7) “Fire In St. Marys” Berlin News Record, January 22, 1912.

(8) The Crescent store advertisement, Spokane Daily Chronicle, December 8, 1919.

(9) Hugh C. McGrath & Co. Athletic Outfitters advertisement, Boston Post, January 19, 1921; Hennepin Hardware Company advertisement, Minneapolis Daily Star, February 6, 1925.

(10) Bridgeport Cycle Co. advertisement, Bridgeport Telegram, January 26, 1922.

(11) Bob Pennington, “$10 can get you a personalized stick,” Toronto Star, November 25, 1974.

(12) “Business Transfer,” Brantford Expositor, July 24, 1933.

(13) “So Many Orders Factory Goes on 24-hour Shifts,” Kingston Whig-Standard, August 11, 1933.

(14) “Result is Always the Same,” Kitchener Daily Record, November 13, 1933.