Harrison Browne had been in many locker rooms throughout his 16-year hockey career. However this one was different. He sat in the locker room surrounded by men. It was his first ice hockey tournament competing as a man after he had transitioned from female to male following his professional career with the National Women’s Hockey League.

He had been in many locker rooms during his career, but this one was different. He was trying to find a space where he belonged after he had transitioned.

Then, somebody dropped an anti-gay slur in the middle of the locker room, and Browne knew this wasn’t a space for him.

Browne found he could be himself on the ice, which is why for 16 years he played ice hockey at all different levels, competing on the women's teams as a woman.

Browne was forced to medically retire after he decided he wanted to begin taking testosterone. Currently, in the United States, President Donald Trump has made several attempts to completely ban transgender athletes in sports. The focus lies mainly on transgender men in women’s sports, however isn’t exclusive to just one group. Browne experienced something different that ended up costing him his athletic career.

He grew up playing ice hockey. The five-foot-five flowy hair’d man with piercing blue eyes found himself on the ice.

The Title Of "Hockey Player" Has Always Been Gender Neutral

He was always surrounded by teammates but felt alone and secluded from other people around him. For Browne hockey was his escape from the world because the term “hockey player” to him was gender neutral.

“I used it as a space where I was just an athlete, I wasn't a boy, I wasn't a girl, I was just among teammates that were hockey players,” he said.

When he started collegiate hockey, he decided he wasn’t interested in hiding who he was anymore. He had known since a young age he didn’t identify as female. He played for the University of Maine’s women’s NCAA team in college, several teams in high school, and then went on to play in the National Women’s Hockey League.

The feelings of uncertainty in his life, however, remained.

As Browne said, “I felt really isolated from everybody else in my school life, in my outside life, I felt like I wasn't truly living until I was on the ice, in a way, and it was just a big solace."

At 20 years old Browne took a huge step in his career. He decided he didn’t want to keep his feelings any longer about his identity. He told his teammates in the third year of college that he wanted to start identifying as he/him.

“The inner hockey world knew my identity. Hockey is a really small world, so the people that I played with and against knew that I was transgender,” he said.

Browne said his teammates weren’t surprised, they just had questions about the next steps. For him, he didn’t plan on taking testosterone yet, which was what the league decided was when he would be forced to switch to a male league. That meant he was allowed to compete in female leagues using he/him pronouns until he began to take hormones.

Following four years at the University of Maine, Browne decided to begin playing professionally, first with the Buffalo Beauts.

He had already come out to his teammates in college. As for his family, his sister, Rachel Browne, suspected from a young age she and her sibling had different interests.

“Growing up we were pretty opposite,” she said. “I was more into figure skating, frilly dresses, makeup. From a young age, he was always into things like, not frilly dresses. He would be more into Tuxedos.”

When he did come out to her, it was no surprise.

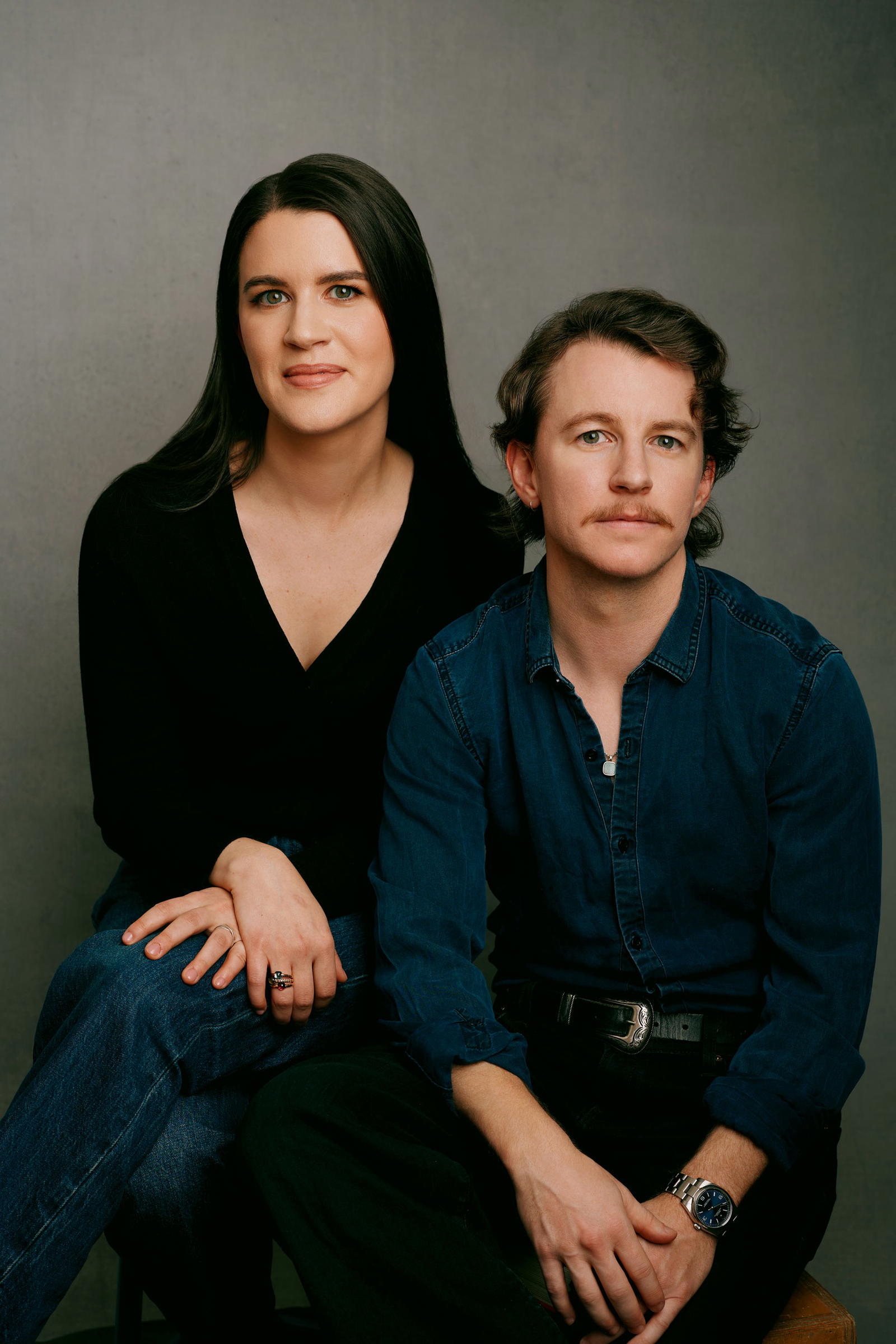

Rachel and Harrison Browne

Rachel and Harrison BrowneBrowne Shown Support From The Women's Hockey Community

In 2016, Brown came out to the public and the media in an interview with ESPN in 2016.

The hockey media’s reaction was positive towards Browne. They understood the situation, and reported on it kindly, acknowledging his new pronouns. He was thrilled at the response, “I wasn't necessarily scared, but I wasn't really sure how it would be received. I was really pleasantly surprised and really welcomed the media attention, because I realized how vital and important trans representation was.”

Browne said that he was confident that the league would support him in coming out. His sister felt similarly. She said, “women's hockey is very LGBTQ+ friendly, so really pushing gender stereotypes and that kind of thing.”

The league needed to come up with a policy for trans players.

Browne worked alongside Chris Mosier, the NWHL, and “You Can Play” to create the first policy in hockey for transgender athletes.

“You Can Play” is a social activism campaign that aims to eliminate homophobia in sports, based on the slogan, "If you can play, you can play." The campaign was launched on March 4, 2012.

He also worked with Mosier, who is the first known out trans athlete to join the United States National Olympic Team different from his sex at birth. He competed as a man in 2015, and 2016 for the United States in triathlons. He began his transition in 2010, however still earned a spot in the 2016 World Championship team.

Browne Paves The Way For Other Transgender Athletes

Dani Rylan, the NWHL commissioner had to do something that hadn’t been done previously. She had to come up with a policy for how to allow transgender athletes to continue to compete in the NWHL.

The guidelines that Rylan created in 2016 can be described in a three page statement saying, the NWHL supports “athletes choosing to express their gender beyond the binary of female and male.” It also stated that an athlete could continue to compete until they decided to start taking hormones.

The rules have continued to stand in the new league, the PWHL, the organization that succeeded the NWHL/PHF.

The PWHL also made a statement on transgender athletes. They said on June 14th, “Our commitment remains steadfast: to build an inclusive league that develops, supports, and elevates the best women’s hockey players in the world by fostering a safe and welcoming environment for our growing, diverse and devoted fan base.”

Still Barriers For Queer Athletes

Although the league accepted Browne at the time, there are still difficulties surrounding their queer athletes today.

Women’s ice hockey has grown exponentially in the past two years with the new creation of the PWHL. However, as the league is split between two countries, United States and Canada, players debate the current state of the league amidst US President Donald Trump's open statements against queer people in sports. Trump has spoken about banning transgender athletes and has been openly against queer marriage, specifically a law that passed allowing it in 2015.

As the league expands and looks for more players, many athletes have opted against joining the PWHL. The league is split between two countries, the United States and Canada. Out of a fear of being drafted to a US team, some prospects for the league have opted out of declaring for varying reasons.

There are currently 159 players in the PWHL and dozens of them are openly gay. This includes several relationships within the league itself including recently married Marie-Philip Poulin and Laura Stacey, and new PWHL Vancouver teammates Michela Cava and Emma Greco among others.

Jackson Continuing The Conversation In The PWHL

In the NWHL, Browne was the only openly transgender athlete. Now, there is a current player in the PWHL, CJ (Carly) Jackson, who identifies as non-binary.

Jackson said growing up they were never sure where they fit.

“As a kid, I didn't see a lot of people who looked like the person that I wanted to look like," said Jackson. "I kind of just kept going down the road of trying to be feminine when I really wanted to have more masculine expressive traits, and because that felt more aligned with who I was.”

Eventually Jackson figured out how they wanted to identify, “I don't think it's like you need to be that person that you see, but you just see someone who's done it some type of way, kind of how I pictured Harrison, right? And then I took that and I did it in my own way.”

Jackson’s career just missed Browne several times, both playing at the University of Maine and with the Buffalo Beauts, and more recently with the PWHL's Toronto Sceptres. They finally crossed paths when Browne was working on a film and needed someone to play his younger self.

Browne was always an inspiration for Jackson.

“Seeing him do it organically just allowed me to make my own path as a queer person,” Jackson said. “Sometimes I try to embody his energy of bravery, right for somebody else, because it's so impactful in my life as a person, let alone a hockey player.”

Athletes in the PWHL fear the political climate in the United States right now, said Ian Kennedy, a hockey writer for The Hockey News.

“In a nation where immigration is under attack, and where LGBTQ+ people are watching human rights evaporate, will international players consider coming overseas?” Kennedy said. “In particular, a large portion of athletes in the PWHL are members of the LGBTQ+ community, so the prospect of joining a league based in a nation where LGBTQ+ rights and healthcare are actively being removed, and where beliefs about the existence of LGBTQ+ individuals are being weaponized and demonized, may give international athletes reason to reconsider.”

As a trans person in hockey, for Browne, this brought up several emotions. He hesitated for a moment and then he said, “it's really, really devastating to see.”

Harrison Brown working on set on his new film alongside CJ Jackson

Harrison Brown working on set on his new film alongside CJ JacksonA New Stage In Life For Browne

Browne has since moved on from ice hockey after he decided to medically retire despite still being in shape to play. In 2018 he decided that he wanted to begin taking testosterone, which meant he was required to leave professional women’s hockey.

Hockey had been his life for as long as he could remember. Browne had never held a job outside of hockey and had always been told what to do, eat and where to be when.

“Suddenly I just had this open schedule, and I really lost myself for a minute after I retired. I think that that's a common story and sentiment felt by a lot of athletes.”

Browne then remembered back when he was with the Buffalo Buttes and a film crew had come in to make a documentary about his transition.

“Scarlett Johansson tried to play a trans man, and there's this huge backlash of cisgender people playing trans characters, and I saw the visibility that I had through hockey, and I wondered if I could do that on a larger scale through acting,” he said.

He began taking acting classes, and then writing scripts featuring trans people.

“I just think that trans people should play trans characters, and trans people should be in writing for these trans characters as well, because we can bring humanity to these characters in a way that a cisgender person just can't innately understand” he said.

He wrote his first short film in 2024 and raised $40,000 from the hockey community through kickstarter.

The film, about a trans man who travels back to his past as his pre-transitioned self and explores an unexpectedly pivotal moment in his transition, premiered in Toronto last year and Browne has found a new passion in telling stories that haven’t been told.

“Filmmaking is now my new obsession, my new love,” he said. “I think my journey through hockey really helped inform this next phase of my life, and I'm forever grateful for it.”

Jackson was featured in the film as a younger version of Browne. Jackson said, “It was one of the most special experiences in my life to be honest, [because I was able] to experience something new, with someone like Harrison, who understood me as a hockey player and a performer in the athletic world.”

Browne’s mission since has been to give younger kids a way to connect with themselves and see themselves in film. He said if he had seen someone like him when he was younger, he would have come out earlier.

He has begun to write stories, films, and scripts highlighting transgender athletes. He travelled the country speaking to groups of people about his experience. He spent time interviewing families of transgender athletes on Capitol Hill fighting for their loved ones rights.

Browne has since found locker rooms where he feels included. He currently plays for Team Trans, a team of transgender women and men that just want to play hockey.

Mason LeFebvre, Vice President of Team Trans, spoke on the importance of having teams where everyone is included. He said, ‘“I always felt a little out of place playing hockey, just in general, at least, like in locker rooms on the ice,” he continued, “being on a supportive team is really important to me and to my mental health, and if I'm on a team that I don't feel supported by whether it's related to gender or not, then I'm just not happy off the ice either.”

Harrison has found ways to keep parts of his hockey life with him, while also creating a new identity as a person.

Coming out helped him feel more comfortable being himself. He said, “I just became sick of hiding. It was enough for me in college to just be out to my close friends, but I needed more. I needed to live my life to everybody as a man.”